How we found our house

I’ve always been interested in architecture. I remember that, as a kid, my dad and I took a few trips driving around New England visiting some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most iconic homes, including Fallingwater.

Nowadays I work as a web developer. It’s a job that, in order to do well, demands a technical skillset as well as strong affinity for design. Architecture is very similar in that way, which is why I think I’ve always been drawn to trades which mix engineering and design. In fact, I had even applied to school as an architecture major at one point and, before switching to software, I had a summer job as a visual design intern.

After graduation, I moved to San Francisco and have been working in tech since. My first job out of college was at a digital agency where I worked with some amazing engineers and had the opportunity to contribute to some really incredible projects. After two and a half years, I moved to a small product-based company, which is where I still am as of March 2023.

As I approached my late 20s, my time working in tech thus far (and a few strokes of luck along the way) had made it possible to build a sizable amount of savings, and so I began entertaining the idea of owning a home. I remember a phone call I had with my dad about it, and upon hearing the steep cost of starter homes in the San Francisco Bay Area, he exclaimed, “you could probably get a Frank Lloyd Wright house for that kind of money!”

I thought to myself, “well yeah, shit, maybe he’s right.”

But I wasn’t sure I wanted to uproot from San Francisco and move to the Midwest just to live in a home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright or some other famous architect. Sure, there are a few Wright homes in the Bay Area, but they weren’t exactly for sale and, if they were, they would be very outside my budget.

This was, however, right around the same time as the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Remote Work

As the pandemic turned from days, to weeks, to months it was becoming obvious that, even if the pandemic were to end tomorrow, remote work had become so normalized that work would seemingly never be quite the same again.

I remember saying to my then girlfriend (now wife) at the time when we were in the drive-thru line at In-N-Out, “if remote work is going to keep being a thing, and I can work from anywhere, maybe I should buy a really beautiful home somewhere else…”

The company I work for was also one of many companies to permanently switch to a largely remote style of working as a result of the pandemic. I now had the opportunity to move just about anywhere in the United States that I wanted, or even to another country for that matter.

As I thought more about it, I realized that San Francisco just wasn’t place I wanted to be anymore. I felt that I needed to settle down and just simplify my life. California also seemed like a risky investment, especially looking ahead to the negative affects of climate change.

This isn’t to say that I regret the time I’ve spent in California. Moving to San Francisco right out of college was absolutely the best decision for me, and I recommend that everyone spend at least some of their young adulthood living in a city. It has availed me of so many opportunities, connections, experiences, and perspectives that I never would have had otherwise.

But by this time it was June 2020, and buying in the Bay Area just no longer seemed right for me. So, I started looking at architecturally significant homes in the Midwest.

Goetsch-Winckler

It all started with the Goetsch-Winckler house, a Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home in Okemos, Michigan, just outside of East Lansing.

I absolutely adored this home, and still do to this day.

The home was built in 1939 for Michigan State University professors Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler. It exemplifies Wright’s trademark styles: long, sweeping horizontal lines, a cantilevered roof, and a symbiosis with nature. Wright even reportedly once called it his “favorite small house.”

I found the listing for the home right as I began my search, but it had already been on the market for a month or so. It was offered at $479k.

Sadly, when I reached out, there was already a pending offer, which ultimately went through. This affected me more deeply than I had anticipated. For weeks, all I could think of was this house — at times even dreaming about it. I felt like I had missed out on the perfect opportunity.

This home was the catalyst for a more determined effort to find the perfect home. I wouldn’t let a home like this slip away again.

I contacted realtors in several states: Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, and Michigan. I also kept my eye on the market in New York and other parts of New England, but I knew my search would end somewhere in the Midwest.

It was also around this time that I signed up for WrightChat, an online forum for enthusiasts of Frank Lloyd Wright and architecture in general.

I followed a post entitled Sure, we can call anything “Frank Lloyd Wright”, which was for sharing homes that weren’t designed by Wright, but felt “Wrightian”. The thread had been running since 2012, and had over 100 pages of replies.

It was here that I discovered the Grabow house.

Grabow

The next house that hit the market which piqued my interest was the Grabow house in Rochester, Minnesota. It was listed in late July of 2020.

Photo via Docomomo US.

The home was built in 1970 and designed by architect John H. Howe (1913–1997), who was was a charter member of the Taliesin Fellowship and Frank Lloyd Wright’s chief draftsman for nearly three decades. Wright’s influence is clearly visible in Howe’s works, but his homes have a personality all of their own.

This was the first time the home had ever been up for sale, as the original owners had lived in the home their entire lives.

It was listed at $750,000, which was a little outside my budget. I ultimately decided not to pursue it, but I was seriously considering it. The home did, however, turn me on to Howe’s work and also encouraged me to consider homes of a similar architectural pedigree—not just exclusively those designed by Wright.

I purchased all books published on Howe’s work, and spent days pouring over Howe’s original architectural drawings which are archived and partially digitized at the University of Minnesota.

Then, I heard about the John Riecker house.

Riecker

Discovering the John Riecker residence and the work of architect Alden B. Dow was a key moment in my home search.

The home had popped up on WrightChat around the same time the Grabow house was listed: For sale: Flood-damaged Alden Dow home - Midland, MI.

On May 19th, 2020, a series of upstream dam failures flooded Midland, Michigan, causing significant damage to a number of homes in the area, including the Riecker house.

In 2013, the home sold for $800k, but since the flood had been listed for just $250k. The interior was gutted, and the house was condemned by FEMA, who required that the home be raised at least one foot above the flood plane.

The price tag was tempting, but ultimately the cost to repair and restore the home was projected to be far too great. I wouldn’t even be able to occupy it until it complied with FEMA’s requirements.

Although it is tragic, the flood did draw my attention to the area and the architecture of Alden B. Dow. So, just like I had done with Howe, I began furiously researching Dow’s work.

Alden Dow

Alden B. Dow (1904–1983) was the son of Herbert H. Dow, the founder of Dow Chemical.

In 1923, Dow attended the University of Michigan to study engineering in preparation to enter his father’s company. But after three years, Dow left to study architecture at Columbia University and graduated in 1931.

Dow studied at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesen architecture studio during the summer of 1933, and opened his own studio in Midland, Michigan shortly thereafter. Although Dow worked under Frank Lloyd Wright for a summer, his work stands entirely on its own.

Dow designed homes for friends, family, and many of the employees of Dow Chemical. There were several other architects working under his employ, and together they helped shaped Midland into the mid-century modern mecca that it is today.

I began working with a realtor (email me for a recommendation!), and researched homes in the area with the help of Mid-Century Modern Midland, a database of architecturally significant homes in Midland designed by Dow, his students, and other notable architects.

During my research, there were two homes which stood out the most to me: the Carras and Ashmun residences.

The Carras residence was designed by Dow in 1961, and was very similar to that of the Riecker.

The home was contracted by Dow Chemical as a research “test” house, intended to integrate a variety of Dow Chemical and Dow Corning products and be constructed using a prefabricated residential panel system. The home was intended to be low-cost and targeted to low- to middle- income families, but ultimately failed in that regard.

This home was not listed on the market (and we did ask!). So that was a no-go.

The other home of Dow’s which was very compelling to me was the Ashmun residence, designed by Dow in 1951 for his cousin, Josephine Ashmun.

It’s an incredible, small A-frame home, which Dow affectionately referred to as the “Timber Teepee”.

The home was originally a single bedroom home, but has had two separate expansions by previous owners over the years.

As incredible as this home would be if it were in its original state, the decisions by previous owners over the years have besmirched its charm—at least for me. If I owned the home, I’d either demolish the expansions, or would never be able to forget that the home I’m living in was “not original”.

But then, I found Red Warner.

Red Warner

Francis E. “Red” Warner received his architectural degree from Pennsylvania State College in 1951, after which he began working under the tutelage of Dow for six years. Then, in 1957, he started his own architectural firm in Midland. His designs were deeply inspired by nature, and were for those who appreciated beauty without extravagance.

Warner used wood extensively. He especially liked the grain and warmth of Douglas fir beams which he incorporated in many of his designs. It was in the small details and practicality of his designs that he excelled. Contractors commented that they could tell it was a Red Warner home the moment they saw the front door.

By contrast, Dow’s designs were sometimes quite eccentric. My wife and I would be looking at his work and, while sometimes we’d love one of his homes, other times it wouldn’t be right for us at all.

Red Warner’s homes tended to be designed using aspects we liked in Dow’s homes, but with a greater influence from Wright’s organic approach to architecture. It was the best of both worlds.

Red Warner is of course no Frank Lloyd Wright. If you’re not from Midland, it’s very likely you have never heard of him. No books have been written about him, none of his homes are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and his name is probably not known outside of the local community and maybe a few hundred hardcore Dow enthusiasts. But I do hope that changes some day.

Information on Warner’s homes was limited but, like with Dow, there were a couple of homes that stood out to me the most.

The first was the Lane residence.

Photo by Preston Jones and Leslie Warner-Rafaniello.

And the other was the Giering residence.

Photo by Preston Jones and Leslie Warner-Rafaniello.

Both had a very similar style, and as I discussed the homes with my realtor, he said:

I just sold an original owner Warner home this past summer… it was before I knew about you!

You would have loved it.

He was referring to the Currin residence.

Currin

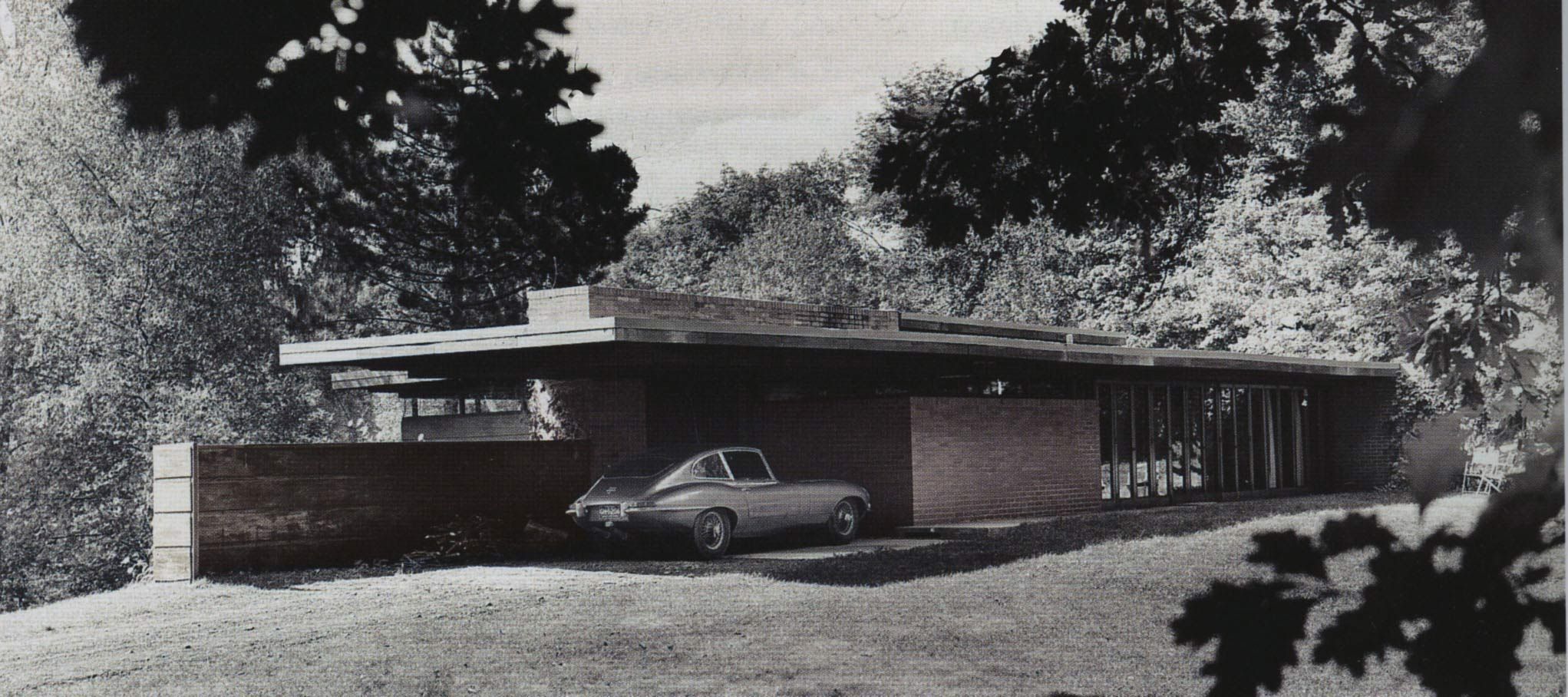

The Currin residence was designed by Warner in 1958 for Cedric and Betty Currin.

Photo by Nathan Buchar.

The Currins were one of Warner’s first clients, and their home is a shining example of mid-century modern design, featuring clean geometric lines, an emphasis on function and livability, and extensive use of natural materials such as Douglas fir, redwood, and field stone from Lake Superior.

When asked about why he contracted Red Warner to design the home, Mr. Currin replied, “I grew up in Wisconsin and had a general familiarity with Frank Lloyd Wright. I looked up architects in the Yellow Pages and saw Warner’s listing. After visiting his own home, and seeing how easy he was to work with, I decided to go with him. And I’m so glad I did!”

The Currins adored their home and lived there for the rest of their lives. Betty passed away in 2016, and three years later, at the age of 88, so did Cedric.

Less than a year later, the flood in Midland led to significant water ingress in the basement. The water finally began to recede after it had reached just six inches below the first floor, but not without first causing one of the concrete walls to buckle.

Due to the extensive damage, the Currin family sold the home for just $115k in September of 2020.

The new owners never occupied the property, and only worked to restore the home. They reconstructed the buckled basement wall, fixed all the wiring, replaced the water heater and furnace, repaired the leaking chimney, and more. However, in August of 2021, one of their jobs was moving out of state, and so they reluctantly decided to sell the home.

My realtor gave me a heads up. And he was right, I did love it.

Photo by Nathan Buchar.

The home needed work, that’s for sure. The entire house had exposed subfloor, the roof needed replacement soon, the kitchen counter tops had been torn up, and the lines for the pool didn’t hold pressure. But for the most part, these issues were merely cosmetic in nature.

The home was listed relatively low, at only $200k. A steal compared to the other homes I had previously considered, but it did need work. The other challenge was that, because the home wasn’t “move-in ready” and had exposed subfloor, mortgage lenders were unlikely to approve a mortgage on it. But I decided I would leave that to chance and, after swaying back and forth on whether I wanted to make an offer, I decided to pull the trigger at the last minute.

There was some interest in the home by architecture enthusiasts like myself, and so I made sure to include an escalation clause with my offer.

On the day that sellers were reviewing offers, my realtor called me.

I have the sellers on the other line so you need to decide in one minute. There’s good news and bad news: You beat out on escalation, but the next highest offer is all cash. You will need to match the all cash offer, and if you do, the house is yours.

It was quite a moment: I had less than a minute to decide whether or not to spend almost the entirety of my life savings to by the home in all cash.

When my wife came home that evening, I asked her how her day was, and then casually mentioned, “oh, and I bought the house.”

Homeowners

In the end, I’m actually extremely happy I ended up paying cash. It wasn’t originally my first option, but not having to worry about a mortgage has given me so much peace of mind that I’m just so thankful for. That said, it’s not lost on me that the position I’ve found myself in is very, very fortunate.

Today, we continue to restore the home back to its original condition. I’m a stubborn purist when it comes to restoration, and “renovation” is a forbidden word in this house. For one project, I spent six months trying to find a laminate counter top which near perfectly matched the original Formica, and I had to import it from Italy!

But seeing the home come back to life has made every ounce of effort worth it.

Thank you for reading. Check out @currinresidence on Instagram to follow along.

Comments